First Semester

The first day of fifth grade I insisted on wearing my hair in what Mother Joyce and I called a peacock bun. She would brush the hair high up on my head and pull it into a ponytail. Starting at the end, she would roll the ponytail into a large “sausage” of hair. She’d then pin the bottom and ends of the sausage neatly to my head. The result looked something like a peacock’s fanning tail, with feathery wisps of hair framing my bespectacled face. Of course, I thought my updo was very chic and mature- a signal I wanted very much to send to my classmates. But more than anything else I wanted to impress my new teacher, a young woman just out of college- a first year teacher! Rumor was this new teacher, Mrs. Burkett (not her real name) was tall, slim, and attractive. I fantasized she also would be hip, smart, and beautiful, and I wanted her to know I could be her protégé.

The first day of fifth grade I insisted on wearing my hair in what Mother Joyce and I called a peacock bun. She would brush the hair high up on my head and pull it into a ponytail. Starting at the end, she would roll the ponytail into a large “sausage” of hair. She’d then pin the bottom and ends of the sausage neatly to my head. The result looked something like a peacock’s fanning tail, with feathery wisps of hair framing my bespectacled face. Of course, I thought my updo was very chic and mature- a signal I wanted very much to send to my classmates. But more than anything else I wanted to impress my new teacher, a young woman just out of college- a first year teacher! Rumor was this new teacher, Mrs. Burkett (not her real name) was tall, slim, and attractive. I fantasized she also would be hip, smart, and beautiful, and I wanted her to know I could be her protégé.

Despite the late summer heat I wore a dark purple print dress that nearly suffocated me in its high peasant collar and long sleeves. At least my ubiquitous saddle oxfords and knee socks were comfortable enough. As Mrs. Burkett explained class rules and procedures in what seemed like slow-motion, I noticed her heavy southern accent. My ears were naturally accustomed to hearing a drawl, but Mrs. Burkett seemed to put extra syllables in every word. “Girr-els,” she said, “will only be allay-ood to the rey-estroo-um one at a tiy-em.” She was indeed tall, thin, and pale as a sheet. Her brown hair was neatly swept into a Marlo Thomas-style flip, which framed her huge brown eyes and square face. She looked like a doe, or possibly a Joan Walsh Anglund character. I wasn’t sure what to think, but one thing I quickly learned: too much talking was definitely not “allay-ood” in Mrs. Burkett’s class. This could mean trouble for a chatterbox like me.

Mrs. Burkett apparently had thought long and hard about her system of punishment, because she was prepared from the first day of school to enforce this system. I thought maybe she was very fond of laws and discipline because her husband was a soldier in Vietnam. A name written on the chalkboard was a warning, and each infraction thereafter meant a check would be added beside the offender’s name. Each check also meant the offender would have to spend ten minutes after school- torture to us kids who cherished the trek through wooded backyards and the nearby creek winding our way home through suburban North Hills. Worse, each subsequent check beside a name would add an extra ten minutes- up to an entire hour! Checks could be issued for many types of infractions: missing homework, not having school supplies, disrespect, running in line, or talking out of turn. This last item was indeed my nemesis. I always had trouble keeping my mouth closed, and it didn’t help that Mrs. Burkett insisted on speaking so slowly and asking such easy questions one-at-a-time. Worse, she never seemed to see my raised hand- even if no one else knew the answer! By late September I had stayed after school a half-dozen times for talking. Once I’d stayed so long I was late for my piano lesson- a big no-no for my strict old piano teacher. As the year settled into a routine, I began to sense something else about Mrs. Burkett- something I had never encountered before- even from a strict old teacher like Mrs. Gamble (not her real name), who’d once made the entire class stand in line for a paddling for making a mess in the cafeteria. No, I began to get a feeling that Mrs. Burkett just didn’t like me, even though I really wanted her to.

My first inkling came one October day when the class was nominating boys to serve as crossing guards on the School Safety Patrol. This job carried the responsibility of assisting kids at crosswalks and intersections by raising and lowering a large yellow-and-black flag . Guards were always upperclassmen, fifth and sixth graders. They wore reflective vests, and they also had the added cachet of leaving class five minutes before the bell at the end of each day. Only top students were allowed to become crossing guards; and since my grades had always been good, I couldn’t understand why this job only went to boys. “Mrs. Burkett, why aren’t there any girls on the School Safety Patrol?” I asked. “Wey-ell Freda, that job has always belonged to the boy-ees.” “Yes, but why can’t girls do it, too?” I pressed on. “Wey-ell,” she paused for a moment, “maybe the girr-els just aren’t stong enough to lift up that flay-ug.” I groaned in protest and blurted out, “Mrs. Burkett, I picked up my fourth grade teacher last year! I’m strong as any boy!” This was true, a few boys and I had tested our prowess by picking up our tiny fourth grade teacher, also a good sport. “Are you a women’s libber, Freda?” The class snickered.

Then there was the adoption incident. One day Mrs. Burkett asked the class for kids who were adopted to raise their hands. I thought this question was somewhat silly; by the time I reached fifth grade all us kids knew who was adopted and who wasn’t. Besides that, I had always been somewhat proud of being adopted, especially since my parents told me how they were “chosen,” and how difficult it was for just anyone to adopt. There were at least fifty parents waiting for every single baby, they said. And I was still a little embarrassed to admit that until kindergarten I had thought all babies were “chosen” for their families as my younger brother and I were. In fact, I thought everybody had to go pick up their babies at a “baby place,” just like we had done from the Greensboro Children’s Home Society when we went there to bring home my brother. So when Mrs. Burkett posed that question to the class, I raised my hand. Of course, I was the only one; I was accustomed to that. Then Mrs. Burkett announced, “Oh Freda! So YOU’RE adopted! I guess your parents can always take you bay-uck if they don’t want you anymore!” The kids laughed, but I didn’t think it was funny at all. I dismissed her comment as plain stupid, as I was beginning to consider her, but it did make me wonder. Had my parents ever thought about taking me back? Did they ever wish another baby had been “selected” for them instead of me? I sure seemed a potential source of trouble these days, always having to stay after school for talking too much. What if my parents didn’t want me anymore? What would I do?

Midterm

By Christmas I was beginning to feel a bit evil, and I began to see the advantage of having a friend in class like Judy Paisley (not her real name), who didn’t like Mrs. Burkett, either. Judy wasn’t a very good student, but she was fun to pal around with, and she was very good in sports. She hadn’t liked Mrs. Burkett’s explanation about the Safety Patrol, either.  In fact, she had a reputation for being tough, which I admired. We often found ourselves together after school, too, and since Mrs. Burkett usually excused herself after the first ten minutes, sometime it left us the better part of an hour to play. “What are you in for today, Judy?” I’d always ask. “Um, not having my homework,” she’d answer. “How about you?” “Same as always, talking.” I’d answer. So we’d usually sit for ten minutes while I helped her with homework. After Mrs. Burkett left, we’d quickly pull out our yo-yos or some string and begin to practice our tricks. She taught me how to “walk the dog.” If we were feeling lucky we’d take out our “clackers,” two noisy acrylic balls suspended on string, and play with those for awhile, while one stood watch near the door.

In fact, she had a reputation for being tough, which I admired. We often found ourselves together after school, too, and since Mrs. Burkett usually excused herself after the first ten minutes, sometime it left us the better part of an hour to play. “What are you in for today, Judy?” I’d always ask. “Um, not having my homework,” she’d answer. “How about you?” “Same as always, talking.” I’d answer. So we’d usually sit for ten minutes while I helped her with homework. After Mrs. Burkett left, we’d quickly pull out our yo-yos or some string and begin to practice our tricks. She taught me how to “walk the dog.” If we were feeling lucky we’d take out our “clackers,” two noisy acrylic balls suspended on string, and play with those for awhile, while one stood watch near the door.

One day Judy and I had an extra-long detention, which led to a discussion of a particular classmate who was one of Mrs. Burkett’s “pets.” This girl, Trish Tate (not her real name), could be a royal pain. She had gotten Judy in trouble for telling Mrs. Burkett she was cheating on a pop quiz. I began to eye Trish skeptically. Why was she always tattling on other kids? I wondered. I knew I was a loudmouth, but never a tattletale. I recalled the day in fourth grade when Trish had gotten two boys in trouble by telling the teacher they’d had a water fight in the bathroom. Judy suggested we give Trish a taste of her own medicine. So we hatched a plot. We would lure Trish into walking home from school with us. Judy knew where there were two chain link fences which separated two back yards. We would suggest this route as a shortcut to Trish, then pin her between the two fences, where we would get to rough her up a bit. I liked the idea, but was worried about hurting Trish in any way. My parents were accustomed to having a blabbermouth daughter, but not a bully. Trish assured me we’d scare her, that’s all. So the appointed day and hour arrived, and Trish agreed to walk home with us. This feat had been surprisingly easy to accomplish. Apparently Trish didn’t have many friends who wanted to walk home with her. As we entered the gap in the fences between the two yards, Judy walked in first, Trish second, and I followed last. Judy stopped midway, and our work began.

Judy went first. “Trish, do you know why we wanted you to walk with us?” Trish had no clue. “Because you need to learn a lesson, and we’re here to teach you!” Trish turned to face me quizically. I didn’t move, but I also didn’t quite know what to say. Judy continued, “Why do you always tell on people? Why can’t you just mind your own business? You made me stay after school because you told the teacher I was cheating.” “But you were,” Trish said timidly. Judy was getting worked up. “That doesn’t matter,” she said, getting very close to her face, “I’m sick and tired of people like you- goody-goodies- who think you’re better than everybody else.” This struck a chord with me. I had helped Trish with her homework, and I’d seen how hard it was for her to do even simple things like contractions. “Trish,” now I was feeling meanness creep in. “How long have we been friends?” Trish thought for a moment. “Since we were in kindergarten at St. Timothy’s, I guess?” “Wrong,” I said. “It’s never. Nobody likes you, Trish, and neither do I. I just pretend to like you ’cause I felt sorry for you, because you don’t have any friends. And if you ever, EVER tell on anyone else again, I’ll tell everybody Judy and I beat you up! Do you want the world to know THAT?” “No,” she said. I could see tears in her eyes. “So what, then?” Judy leaned in close to Trish. Their noses almost touched. “So I’ll leave you alone,” Trish said meekly. Judy slowly walked to the edge of the gap in the fences. She stopped just short of the opening. I could tell Trish wanted to run away. “What’s that again?” I yelled it this time. “I promise not to tell on you anymore!” Trish choked on a sob. Judy stepped aside ever so slightly, letting Trish past, but not before giving her a sharp shove as she began to run away. As Trish sped across the yard, my heart racing as fast as she ran, I began to wonder, “Have I turned into a bully?”

Second Semester

After Christmas I vowed to return to school a new woman. From Santa I had received a poncho, Carl Sandburg’s biography of Abraham Lincoln, and some socks. I also had gotten an adult coin collecting set: a kit that included a coin valuation book, some albums for my Lincoln cents, a magnifying loupe, a set of cardboard coin holders, tweezers, and some coin tubes. From my mother, however, I received the gift I’d been yearning for since school had begun: my first bra. When school resumed I was pleasantly surprised at some changes the fifth grade teachers had decided to make. No longer would my class spend all day with Mrs. Burkett; instead, we would begin “switching” classes for Language and Math. I would have Miss Black (not her real name) for Language every morning for two hours with the other good readers. Finally, it seemed, school began to click into place, as it always had in my past. Even though the S.R.A. Reading kits were nothing more than boring boxes of story-cards with multiple choice quizzes on each story, I relished Miss Black at least allowed us to talk and move around the room every once in awhile. Mrs. Burkett, too, seemed to have relaxed some after the holiday. By early spring, she had actually brought her Simon and Garfunkel album to school and played it for the class.

After Christmas I vowed to return to school a new woman. From Santa I had received a poncho, Carl Sandburg’s biography of Abraham Lincoln, and some socks. I also had gotten an adult coin collecting set: a kit that included a coin valuation book, some albums for my Lincoln cents, a magnifying loupe, a set of cardboard coin holders, tweezers, and some coin tubes. From my mother, however, I received the gift I’d been yearning for since school had begun: my first bra. When school resumed I was pleasantly surprised at some changes the fifth grade teachers had decided to make. No longer would my class spend all day with Mrs. Burkett; instead, we would begin “switching” classes for Language and Math. I would have Miss Black (not her real name) for Language every morning for two hours with the other good readers. Finally, it seemed, school began to click into place, as it always had in my past. Even though the S.R.A. Reading kits were nothing more than boring boxes of story-cards with multiple choice quizzes on each story, I relished Miss Black at least allowed us to talk and move around the room every once in awhile. Mrs. Burkett, too, seemed to have relaxed some after the holiday. By early spring, she had actually brought her Simon and Garfunkel album to school and played it for the class.

One day Miss Black’s and Mrs. Burkett’s Language classes were watching a filmstrip together, as we sometimes did. Some kids were allowed to sit on the floor, and Mrs. Burkett asked the girls, as she often did during filmstrips, for volunteers to scratch her back. I raised my hand offhandedly, never expecting to be chosen, but on this occasion she called my name. I almost jumped out of my chair. I gingerly approached her at her desk, where I scratched and scratched until the end of the filmstrip. I figured Mrs. Burkett’s gesture must have meant I had finally won her favor. Days passed, and on another occasion Miss Block’s and Mrs. Burkett’s students had a spelling bee one Friday morning. I was excited, since I was usually one of the top spellers. The action began slowly at first, but soon the competition was fast and furious as spellers began missing words. Finally, there were four of us left, then three. Mrs. Burkett gave the word: shepherd. I spelled it. “No, Freda, I’m sorry. You’re ee-in-correct.” I knew I had spelled it correctly, and I protested. “Now Freda, see-ince you’re so smart, spell it agay-in.” I spelled it again, correctly. “No, that’s wro-ung.” “I’m NOT WRONG!” I shouted, writing it on notebook paper as I called out the letters. “See? It is S-H-E-P-H-E-R-D!” I held up the paper to make my point. “Wro-ung!” she shouted back “its S-H-E-P-A-R-D!” I looked around for someone, anyone, to save me. Miss Black, unfortunately, was out of the room for a smoke break, so there was no one. I huffed back to my chair, utterly demoralized.

After school that day Mrs. Burkett continued her conversation. “Now Freda, I will not have you being rude and sassy!” “But Mrs. Burkett, you spelled shepherd wrong. You spelled it s-h-e-p-a-r-d.” There was a pause. “No, Freda, you’re wrong. That’s how YOU spelled it!” This took the cake. Now she was turning her poor spelling against me. “Mrs. Burkett, you’re not fair! That’s NOT how I spelled it and you KNOW it! YOU’RE the one who spelled it that way! I wrote it down! I have witnesses!” This last comment was obviously too much. “FREDA ZEH! YOU are lying.” Now it was my turn. “Mrs. Burkett, MY MOTHER is a school supervisor! I’ll tell HER about this and I’ll let HER decide who’s lying!” That was it. She told me to go home, which I did in record time. All the while I knew the clock was ticking as I prepared myself for the inevitable phone call I knew Mother Joyce would receive later that night.

Three days later Mrs. Burkett arrived at my parents’ home at 4:30 in the afternoon. Mom had to leave work early to be home by that time, so I knew she wouldn’t be in the best mood. I had tried in my most sensible voice to explain to her what had happened during the spelling bee- even producing the sheet of notebook paper with the word, “shepherd,” I’d written- as evidence. Mrs. Burkett rang the front doorbell, and Mom dismissed me to my bedroom, she said, “at least for the first part of our conference.” I went upstairs and closed my door, but strained against it to try to overhear what they were saying. Finally after about fifteen minutes I had given up, so I went back to the “S” volume of my World Books and was re-reading the article on spiders when I heard Mother Joyce call my name. “Freda, could you join us in the living room?” “Sure, Mom, I’ll be right down.” My heart was pounding so hard I could feel my chest rattle. As I walked into the living room, Mrs. Burkett and my mother were each drinking a cup of coffee. They seemed pretty relaxed. “This is a good sign,” I thought.

“Freda, Mrs. Burkett tells me you are a very bright student,” my Mom began. Mrs. Burkett picked up as if on cue. “Yay-yes, Freda, you are soo smart. I just luh-ve having you in my clay-uss.” Something seemed wrong; Mrs. Burkett never acted this nice, even when our principal Mr. Mallette was visiting class. Mom continued, “Freda, I think Mrs. Burkett has something to tell you.” Mrs. Burkett said, “Freda, I’m soo sorry I didn’t give you credit for spelling that word riy-ught. Your mom showed me you’d written it day-oun, and I didn’t give you credit for spelling it riy-ught. I’m sooo sorrr-ry.” “That’s okay,” I said. Much later, I realized she’d failed to apologize for spelling it incorrectly herself , accusing me of her mistake, and then calling me a liar, but Mom continued. “But Freda, we may have another problem here, a much larger problem.” I couldn’t imagine what she was talking about. “Mrs. Burkett says you popped her bra.” “I WHAT?” I was aghast. “Yay-yes, when you were scratching my back during the filmstee-ip.” Mom added in a measured tone, “Now Freda, we understand you are a developing girl, and you may have curiosity about adults and their bodies, but it is unacceptable to play with your teacher’s bra.” “But, Mom! I…” I pleaded before she interrupted me, “I think you owe your teacher an apology.” I was utterly vanquished. “I’m sorry, Mrs. Burkett, for popping your bra,” I lied, gritting my teeth to hold back tears. “Oh Freda, thay-unk you for your apology. I forgee-ive you.”

Year End

As the school year spun to a close, the kids in Mrs. Burkett’s class were upbeat. Next year we’d be in sixth grade- at the top of the school after six long years at E.C. Brooks Elementary. President Nixon was allowing the U.S. table tennis team to go to China that spring, which prompted everyone to go around yelling, “King Kong went to Hong Kong to play ping-pong with his ding-dong!” I certainly was getting antsy; the end of the year was in sight, and Lord willing, I would survive fifth grade. After the spelling bee I had tried my best to lay low and avoid saying much of anything to Mrs. Burkett unless absolutely necessary. Of course, this task was impossible; she was my teacher after all. Several instances cropped up to remind me Mrs. Burkett had not finished with me- yet.

First, there was the thumbtack Leslie Overman (not her real name) put in my chair. I discovered her red-handed leaning over with a tack in her hand. When I caught her by surprise, she quickly blurted out, “Mrs. Burkett told me to do it! I swear!” “Yeah, right,” I glared at her, “sure.” but I wondered. Then there was a time the class was working on our Social Studies project about our chosen state. Mine was Wyoming. I was putting the finishing touches on my buffalo flag while Mrs. Burkett was walking by. “Freda,” she said as she patted my back, “thay-et’s verry nah-ice.” A few minutes later Stuart Brooks (not his real name) walked by my desk and cuffed me on the shoulder, hard. “Stuart!” I yelled. “What on earth?” He was laughing so hard he could hardly talk, “Can’t you read?” he said choking back laughter. I had no idea what was wrong with him. Soon after, two other boys did the same thing. Each said, exploding with yuks, “Can’t you READ?” I thought everybody had lost their minds. Finally, Tim Morrison whispered to me, “Your back, Freda, on your back” he pointed toward my back. I reached behind my back and pulled off a taped sign that read in Mrs. Burkett’s cursive script, “Hit Me.”

Finally, school was almost over. I had long finished all the S.R.A. kits and had also completed several projects with Tim and a few other kids on North Carolina birds, the Civil War, and had done an independent book report on the book, My Friend Flicka, as part of my Social Studies project. One day Mrs. Burkett told the class they could have free reading time and could sit anywhere they wanted. “ANYwhere?” I asked Mrs. Burkett, hoping to be sure. “Yay-yes, anywhere.”

I had spied the empty cabinet under the sink on several occasions. It appeared to have the width of a laundry basket and was at least twice as deep. This spot seemed a rather daring, independent, yet private place to carry on my reading, so I wedged myself into the cabinet, much to the delight of several onlookers, including Judy Paisley, who just shook her head and grinned. Of course, I had left the cabinet door cracked in order to have enough light to see, but I was otherwise cozy in my improvised book nook. Suddenly, the door slammed shut. No sooner than that, I also heard a tremendous commotion that sounded like a tornado had crashed into class- desks scraping, voices shouting- utter chaos! Alarmed, I shouted, “Hey! What’s going on?” More scraping and shouting. “LET ME OUT! WHAT’S HAPPENING!? LET ME OUT!!!” I panicked. I began kicking the door, which seemed to slam back each time I attempted to kick it open. Finally, with both legs, I pushed the door open with all my might. CRRRAACK! The hinges broke and wood splintered simultaneously as I kicked off the door. The sight was astonishing. The entire class, it appeared, had piled their chairs in front of the cabinet door. I could see kids jostling each other and laughing. In back stood Mrs. Burkett, leaning over with a huge ear-to-ear smile. I had no doubt what had happened. She’d told the class to do it.

The very last day of school, I recall, the students from our two fifth grade classes loaded into Miss Black’s room and sang along to the record player. Someone had brought a 45-r.p.m. single of the Three Dog Night hit, “Joy to the World,” which we belted out at full volume.

Read Full Post »

The first day I reported to work at the Hargraves Center, I discovered my vision of diversity was a pipe dream. In fact, I was the only Caucasian in the whole facility, which had something like four hundred campers, ages five to sixteen, and a staff of thirty-some counselors. I stood out like a Q-tip in a chocolate box. “Hey, who that white lady?” one young camper shouted when his group was delivered to their first arts and crafts class. “Shhh! Hush your mouth!” his counselor scolded. “She’s your arts and crafts teacher.” “Ooooh” he squealed, “art and craft!! What that?” After numerous introductions that pretty much followed a similar script, I began to feel a little like the punchline in someone else’s joke.

The first day I reported to work at the Hargraves Center, I discovered my vision of diversity was a pipe dream. In fact, I was the only Caucasian in the whole facility, which had something like four hundred campers, ages five to sixteen, and a staff of thirty-some counselors. I stood out like a Q-tip in a chocolate box. “Hey, who that white lady?” one young camper shouted when his group was delivered to their first arts and crafts class. “Shhh! Hush your mouth!” his counselor scolded. “She’s your arts and crafts teacher.” “Ooooh” he squealed, “art and craft!! What that?” After numerous introductions that pretty much followed a similar script, I began to feel a little like the punchline in someone else’s joke. The first day of fifth grade I insisted on wearing my hair in what Mother Joyce and I called a peacock bun. She would brush the hair high up on my head and pull it into a ponytail. Starting at the end, she would roll the ponytail into a large “sausage” of hair. She’d then pin the bottom and ends of the sausage neatly to my head. The result looked something like a peacock’s fanning tail, with feathery wisps of hair framing my bespectacled face. Of course, I thought my updo was very chic and mature- a signal I wanted very much to send to my classmates. But more than anything else I wanted to impress my new teacher, a young woman just out of college- a first year teacher! Rumor was this new teacher, Mrs. Burkett (not her real name) was tall, slim, and attractive. I fantasized she also would be hip, smart, and beautiful, and I wanted her to know I could be her protégé.

The first day of fifth grade I insisted on wearing my hair in what Mother Joyce and I called a peacock bun. She would brush the hair high up on my head and pull it into a ponytail. Starting at the end, she would roll the ponytail into a large “sausage” of hair. She’d then pin the bottom and ends of the sausage neatly to my head. The result looked something like a peacock’s fanning tail, with feathery wisps of hair framing my bespectacled face. Of course, I thought my updo was very chic and mature- a signal I wanted very much to send to my classmates. But more than anything else I wanted to impress my new teacher, a young woman just out of college- a first year teacher! Rumor was this new teacher, Mrs. Burkett (not her real name) was tall, slim, and attractive. I fantasized she also would be hip, smart, and beautiful, and I wanted her to know I could be her protégé. In fact, she had a reputation for being tough, which I admired. We often found ourselves together after school, too, and since Mrs. Burkett usually excused herself after the first ten minutes, sometime it left us the better part of an hour to play. “What are you in for today, Judy?” I’d always ask. “Um, not having my homework,” she’d answer. “How about you?” “Same as always, talking.” I’d answer. So we’d usually sit for ten minutes while I helped her with homework. After Mrs. Burkett left, we’d quickly pull out our yo-yos or some string and begin to practice our tricks. She taught me how to “walk the dog.” If we were feeling lucky we’d take out our

In fact, she had a reputation for being tough, which I admired. We often found ourselves together after school, too, and since Mrs. Burkett usually excused herself after the first ten minutes, sometime it left us the better part of an hour to play. “What are you in for today, Judy?” I’d always ask. “Um, not having my homework,” she’d answer. “How about you?” “Same as always, talking.” I’d answer. So we’d usually sit for ten minutes while I helped her with homework. After Mrs. Burkett left, we’d quickly pull out our yo-yos or some string and begin to practice our tricks. She taught me how to “walk the dog.” If we were feeling lucky we’d take out our  After Christmas I vowed to return to school a new woman. From Santa I had received a poncho, Carl Sandburg’s biography of Abraham Lincoln, and some socks. I also had gotten an adult coin collecting set: a kit that included a coin valuation book, some albums for my Lincoln cents, a magnifying loupe, a set of cardboard coin holders, tweezers, and some coin tubes. From my mother, however, I received the gift I’d been yearning for since school had begun: my first bra. When school resumed I was pleasantly surprised at some changes the fifth grade teachers had decided to make. No longer would my class spend all day with Mrs. Burkett; instead, we would begin “switching” classes for Language and Math. I would have Miss Black (not her real name) for Language every morning for two hours with the other good readers. Finally, it seemed, school began to click into place, as it always had in my past. Even though the S.R.A. Reading kits were nothing more than boring boxes of story-cards with multiple choice quizzes on each story, I relished Miss Black at least allowed us to talk and move around the room every once in awhile. Mrs. Burkett, too, seemed to have relaxed some after the holiday. By early spring, she had actually brought her Simon and Garfunkel album to school and played it for the class.

After Christmas I vowed to return to school a new woman. From Santa I had received a poncho, Carl Sandburg’s biography of Abraham Lincoln, and some socks. I also had gotten an adult coin collecting set: a kit that included a coin valuation book, some albums for my Lincoln cents, a magnifying loupe, a set of cardboard coin holders, tweezers, and some coin tubes. From my mother, however, I received the gift I’d been yearning for since school had begun: my first bra. When school resumed I was pleasantly surprised at some changes the fifth grade teachers had decided to make. No longer would my class spend all day with Mrs. Burkett; instead, we would begin “switching” classes for Language and Math. I would have Miss Black (not her real name) for Language every morning for two hours with the other good readers. Finally, it seemed, school began to click into place, as it always had in my past. Even though the S.R.A. Reading kits were nothing more than boring boxes of story-cards with multiple choice quizzes on each story, I relished Miss Black at least allowed us to talk and move around the room every once in awhile. Mrs. Burkett, too, seemed to have relaxed some after the holiday. By early spring, she had actually brought her Simon and Garfunkel album to school and played it for the class.

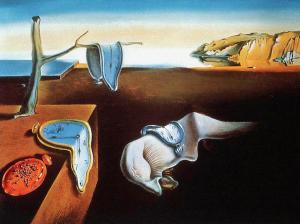

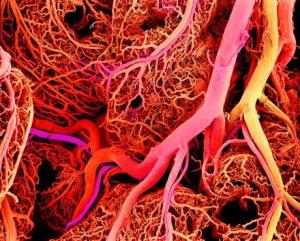

From top to bottom: Amazon river and its tributaries from space; Blood vessels and capillaries magnified many times; Cloud-to-cloud lightning; Crab Nebula, first observed in 1054 by Chinese astronomers; Tree branches showing dendritic growth patterns; Rilles on Titan, one of Saturn’s moons; Photomontage by artist Ahmed ibn Ibrahim

From top to bottom: Amazon river and its tributaries from space; Blood vessels and capillaries magnified many times; Cloud-to-cloud lightning; Crab Nebula, first observed in 1054 by Chinese astronomers; Tree branches showing dendritic growth patterns; Rilles on Titan, one of Saturn’s moons; Photomontage by artist Ahmed ibn Ibrahim Then my friend Kelly got a 10-speed bike for Christmas, and I got the idea what was necessary to be cool was a bike. And not just any bike either, a 10-speed bike. In the run-up to my birthday that spring I began peddling the concept to my parents I really needed a ten-speed bike, a proper, safe, road bike to provide transportation to and from school. I neglected to mention anything about a 10-speed bike boosting my coolness factor, but I calculated that line of reasoning wouldn’t advance my cause, so I went with the safety route, sure to touch their pragmatic sensibilities. I assured them a bicycle would eliminate the need for me ever to bum a ride to school again. They seemed warm to the notion, and one day my father suggested we go to Sears after school to look at bikes. Mortified, I would have none of it. Kelly’s bike was a Raleigh, a British-made beauty of elegant proportions. No, I explained emphatically, Sears or Schwinn did not produce the right type of bike. No domestic manufacturer, in fact, made adequate bicycles. “These days,” I explained, “only Europe makes a safe road bike.” My parents eyed me and each other skeptically, but I continued, “I think

Then my friend Kelly got a 10-speed bike for Christmas, and I got the idea what was necessary to be cool was a bike. And not just any bike either, a 10-speed bike. In the run-up to my birthday that spring I began peddling the concept to my parents I really needed a ten-speed bike, a proper, safe, road bike to provide transportation to and from school. I neglected to mention anything about a 10-speed bike boosting my coolness factor, but I calculated that line of reasoning wouldn’t advance my cause, so I went with the safety route, sure to touch their pragmatic sensibilities. I assured them a bicycle would eliminate the need for me ever to bum a ride to school again. They seemed warm to the notion, and one day my father suggested we go to Sears after school to look at bikes. Mortified, I would have none of it. Kelly’s bike was a Raleigh, a British-made beauty of elegant proportions. No, I explained emphatically, Sears or Schwinn did not produce the right type of bike. No domestic manufacturer, in fact, made adequate bicycles. “These days,” I explained, “only Europe makes a safe road bike.” My parents eyed me and each other skeptically, but I continued, “I think  I knew DeVon Hughes (not his real name) would eventually be in my class from the first day I heard Assistant Principal John Doe (see prior post) mention his name. “Mark my words, THAT ONE’LL be an axe-murderer!” Mr. Doe pronounced. Doe’s prognostication ricocheted down the halls of the elementary school as fast as a proverbial speeding bullet, due in part to DeVon launching a temper tantrum of such epic proportions that he left a classroom in shambles, a bunch of kids stunned speechless, and a teacher so terrified she’d threatened to quit “if anything ever happened like that again.” Even Mr. Doe seemed awed by DeVon’s ability to foment controversy and chaos, and the worst part was this: Doe didn’t know how to stop him.

I knew DeVon Hughes (not his real name) would eventually be in my class from the first day I heard Assistant Principal John Doe (see prior post) mention his name. “Mark my words, THAT ONE’LL be an axe-murderer!” Mr. Doe pronounced. Doe’s prognostication ricocheted down the halls of the elementary school as fast as a proverbial speeding bullet, due in part to DeVon launching a temper tantrum of such epic proportions that he left a classroom in shambles, a bunch of kids stunned speechless, and a teacher so terrified she’d threatened to quit “if anything ever happened like that again.” Even Mr. Doe seemed awed by DeVon’s ability to foment controversy and chaos, and the worst part was this: Doe didn’t know how to stop him.